My Reading Life: Heather B. Armstrong

Recently, I dug out my trusty (and dusty, and dead) Kindle, recharged it, and used it to preview some files I was working on for a client.

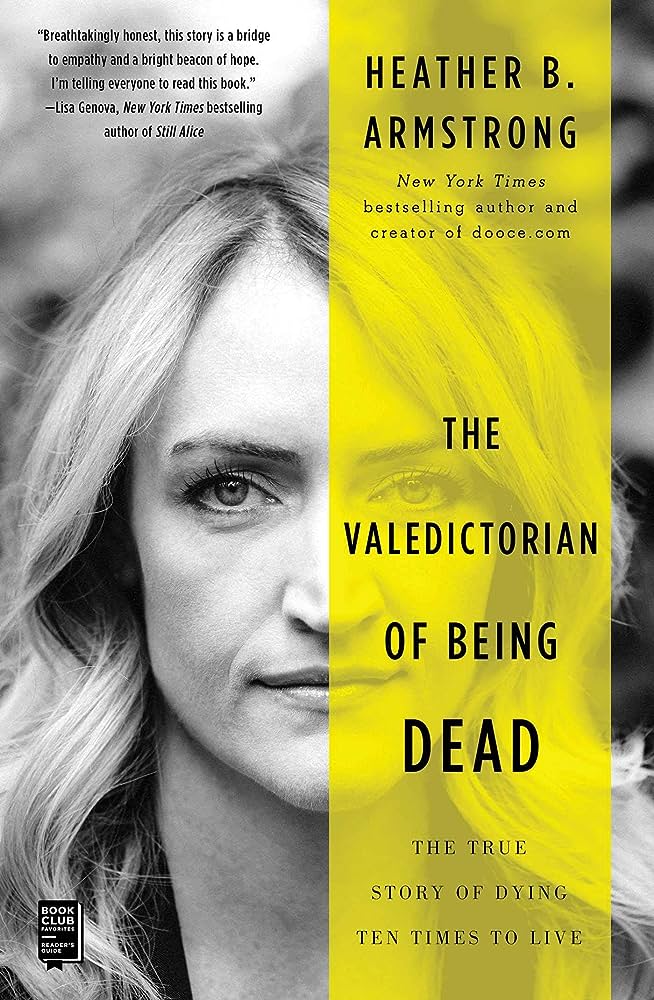

One of the books languishing on my Kindle’s homepage was The Valedictorian of Being Dead by Heather B. Armstrong.

I thought, not for the first time, I’m pretty sure this is the same person who wrote It Sucked and Then I Cried, a memoir about postpartum depression that I read on my honeymoon (romantic, right?)

I decided to look her up real quick and confirm that it was in fact the same woman. (I really enjoy reading multiple memoirs by the same author and putting together the trajectory of a life.) But the first result that popped up read: Heather Brooke Armstrong (née Hamilton; July 19, 1975 – May 9, 2023) was an American blogger …

Was.

Heather committed suicide mere weeks before I decided to look her up again. The Valedictorian of Being Dead. I felt a twisting in my heart for her two children and I began reading the book that day.

Two years ago, I received a text from a friend letting me and other close friends know that a college classmate had recently died. She had an elementary-aged child and a newborn. It didn’t take too long for one of us to ask the question we had all been thinking, and the friend who gave us the news confirmed that, yes, she had committed suicide while in the grip of postpartum depression. Mere days after posting smiling photos of her family on the campus where we all went to college. And, if her maternity leave from her medical practice was the standard American fare, her death came right around the time she would have been returning to work.

As I viewed the last photos her husband posted and re-read the texts and read the stories shared on a fundraising page for her children’s future, my husband told me I should stop “dwelling” on her death. I had hardly known her in college, and her death didn’t impact me in any “real” way.

Except that in her life I saw my friends who were mothers of young children. In her life I saw me. For although I had never considered taking my life, I was slowly emerging from what had been the hardest year of my life. My first year as a mother of two, spending endless days trying to meet the constant needs of a baby and a three-year-old, sleep-deprived, losing my temper more often than I’d like to admit (and hating myself for it), hundreds of miles away from my dearest friends whom I hadn’t seen in almost two years. Because did I mention that we were in the middle of a pandemic? A pandemic that made me feel guilty for sending my older son to part-time preschool or allowing carefully vetted (and vaccinated) caretakers into my home once a week or more so that I could take a shower in peace or nurse my baby undisturbed. I didn’t know if I had postpartum depression of if this was just par for the course, having a new baby in a pandemic. I didn’t know if other mothers were struggling as much as I was. But I did know this: I had glimpsed the dark place my classmate had been in, and it broke me inside to know she couldn’t find a way out.

When my husband later apologized for being dismissive of my need to process the death of a woman I hardly knew, he told me it was because he was “terrified” of the idea that I could relate to her and he needed to push such realities away.

My best friend and I, both vaccinated, decided that we would chance an in-person meeting with our children that summer, meeting halfway between our respective homes. Like the classmate who had died, my best friend also bore the weight of a demanding career, of being the main breadwinner for her family, and of young children cooped up at home during the pandemic. I had discussed it with my husband, and there was one thing I needed to make sure she knew before that weekend was over. That if she ever found herself in that dark place, I would pack up my kids and cross the states between us and I would be there. Because nothing could be worse than that. Than a dead mom.

Suddenly every judgmental thought I had ever had about other mothers came back to haunt me. I made a vow then to do my best to break the toxic cycle of mom-shaming, even if such shaming happened only in my own mind. Because I don’t know what other mothers are grappling with that drives them to make the choices they do.

Too much screentime for the kids? Mom distracted by her phone? Long hours spent in childcare? Boxed mac and cheese again for dinner? Posting constantly on social media to “prove” what a good parent you are?

Who cares? WHO CARES? Because moms are doing whatever they can to get through the day and carry their secret burdens and stay in this world to kiss their children goodnight. And sometimes, we just have to let that be enough.

Heather B. Armstrong was dubbed “Queen of the Mommy bloggers” for her candid blog posts about her parenthood journey. For many, many mothers, she was one of the few antidotes to rampant mom-shaming. By writing honestly about the scarier sides of motherhood, about what it was like to mother while depressed, mother while addicted, mother while imperfect, sprinkling her sarcasm and dark humor throughout, she reminded thousands if not millions that they were not alone. And she endured — you guessed it — shaming and disdain for it. People who knew her surmised that this contributed to her decision to end her life. So, if saying nasty things to or about someone in a public forum makes you feel better about yourself, maybe think twice about hitting send.

In the Valedictorian of Being Dead, Heather writes about how she agreed to be part of an experimental treatment for depression that entailed being put into a coma — flatlining her brain waves — ten times in the span of a couple months. She agreed to it because she was suffering through what had been her worst depressive episode to date. Nonetheless, she writes sentences like this one frequently throughout the book: “I knew that I would not ever attempt to take my life, although I wanted nothing more than to be dead.” (emphasis mine)

Because I read this after Heather had already died, passages like this one struck me differently. I wondered if she wrote them to convince herself. I wonder if she wrote them to convince her ex-husband and the rest of the public that she was a fit mother, since one of her biggest fears was that her children would be taken from her. And I wonder how many times her mother and her children returned to passages like that one to reassure themselves that she wouldn’t leave them. At least, not like that.

She encounters a lot of people in the course of her treatment who are skeptical, who think that she’s either incredibly brave or crazy for participating in the study. When I told a friend about the book, she looked skeptical. “Has she tried regular therapy? EMDR?” Heather claims neither bravery nor insanity, simply desperation. I understood this, too. So did those who loved her most, which is why they supported her participation in the study.

I’m fortunate that I have never encountered a depressive episode as bad as Heather’s. But I do know what it’s like to live with a chronic, sometimes debilitating condition. I’ve had frequent migraines since I was 15 (a physical condition comorbid with depression and anxiety), and I have tried so many things to remove the specter of migraine from my life. Medications. Dietary changes. Acupuncture. Chiropractic. Meditation. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy. Neuromodulation devices. Journaling. Most of it has helped some. None of it has removed the burden from my life, only lessened it. Similar to Heather, I feel an increasing desperation to “solve” this problem now that I have young children. If a doctor approached me asking me to be part of a promising study on curing migraines that involved going into a coma 10 times, I would ask him if he had a pen handy.

I wonder if this affects the reception of the pilot study’s outcomes. I wonder if Heather could have had access to these treatments again, had she contacted her psychiatrist. Now that she is gone, this second memoir of her depression stands as a memorial to the struggle that ultimately claimed her life. It raises more questions than answers, despite the clean narrative arc, complete with an epilogue in which she informs the reader she has not wanted to be dead once since completing the experimental treatment.

I didn’t know Heather beyond her public persona. Two memoirs and an occasional blog post. But I’m still so sorry that she succumbed to the lie that the world would be better off without her.

It isn’t. And it’s not better off without you, either, no matter the lie your brain might be telling you. Do what you need to do. Put your kids in front of the TV. Eat too many cookies. Call your mom, your best friend, your pastor, your doctor. Just stay with us, for as long as you can.

And for the rest of you: turn your judgment dial down to 0.

I’ll try to do the same.