My Reading Life: Boymom by Ruth Whippman

I always thought I would be a mother of girls.

My future dreams of children always featured girls — often two. I grew up in the middle of two sisters, no brothers. My husband grew up the only boy in his family, with three sisters. I spent the first half of my career working for New Moon Girl Media, which published a feminist magazine for girls. Being able to put everything I’d learned to use by raising girls seemed inevitable.

I had no brothers, few male friends (none of whom I was emotionally close to), and only a handful of dating relationships with men that fizzled out pretty quickly. For most of my life, boys and men still felt very much like “the other,” a type of human I could never quite understand.

When I was pregnant with my first child, we decided not to learn the sex. I picked out a girl name, and my husband picked out a boy’s name. His boy’s name was acceptable to me, but I didn’t spend much time negotiating it because OF COURSE I WAS HAVING A GIRL. My family shared this assumption. During a gender guessing game at my baby shower, almost everyone I had invited guessed, “girl.” My husband’s guests included more mixed predictions.

You probably know how this story ends. I am mother of not one, but two boys. I will never have the daughter I always assumed was my due. This makes me sad sometimes, but most of the time doesn’t matter.

In those first moments in the operating room where my older son had been delivered by C-section, the new-parent, “Oh God, I don’t know what I’m doing” feeling was compounded. I thought, I know NOTHING about boys. I thought, My husband is a good man, and even if I really mess this up, he’ll turn out okay if he just emulates his dad, right?

Within a few days, my son’s sex was irrelevant. I fell deeply in love with him, laying beside him in bed and watching him sleep and thinking somehow I had birthed the perfect baby. (I thought the same thing when my second son was born. How was it possible for one couple to produce TWO of the world’s most perfect babies?!? Okay, I know all parents feel this way. And the human race is better for it.)

Although books are usually my go-to when I feel uncertain or in need of validation, I didn’t seek out books about raising boys. I followed my instincts, which led me to breastfeed into toddlerhood, cosleep (okay, this was more desperation than instinct), snuggle while reading aloud, and engage in exuberant outbursts of affection. (I now often hear my younger son exclaiming as he hugs a stuffy, “I love you so much!!” in an echo of my words when I give him an impromptu squeeze.)

My one concession to the lingering fear that I didn’t know what the heck I was doing came in my reading Pink Brain, Blue Brain: How Small Differences Grow Into Troublesome Gaps (and what we can do about it) by Lise Eliot. The takeaway was that, while biological differences do exist between the sexes, they are minor. We do our kids a disservice by constantly reinforcing these differences and limiting their eventual range of skills and confidence. Perhaps nowhere is this more troubling than in the areas of emotional and relational intelligence, where women perform a disproportionate amount of the emotional labor and men suffer from lack of authentic connection.

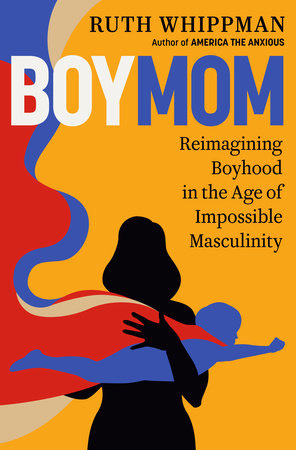

I had been a boy mom for seven years when Boymom: Reimagining Boyhood in the Age of Impossible Masculinity by Ruth Whippman arrived on the scene. I came across it in an article my mom had sent me about academic redshirting (holding kids back a year before they start Kindergarten), which is very common in my community. My husband and I opted not to do it despite both our sons having summer birthdays and being fated to be the youngest in their classes—sometimes by up to two years. Our decision was partially based on the research cited in Pink Brain, Blue Brain, which I reread during the agonizing two weeks that we considered whether we would reject the school’s recommendation that we redshirt our oldest son. I also just had this sense that the pervasive redshirting of boys with summer birthdays was a way of saying, “You’re a boy — we just don’t expect that much of you,” and I balked at that assumption.

I started hunting down BoyMom immediately. I don’t know why this sense of urgency compelled me, except perhaps to believe there is some God of Books who was guiding me past the literally thousands of other books vying for my attention in my TBR.

Whippman’s story was immediately recognizable to me. Writer who grew up steeped in feminist ideology now raising three boys in the midst of a culture that has come to prefer girl children. Mother who was very aware of the abuses perpetrated by the patriarchy, wanting her children to pursue happiness and opportunity without becoming entitled little pricks. Mother who cared about the challenges facing girls and women, but needing to make space to understand the challenges facing boys and men, too. Mother who understood this wasn’t a “fight” or a zero-sum game.

The research cited in BoyMom reveals that boys, are, in fact, harder to care for. Boy babies cry more often than girl babies and need more soothing. (The endless books on sleep I read when my firstborn was an infant also revealed that they are poorer sleepers in their early years.) Yet, despite this increased need, parents often give their boy children LESS soothing, holding, and affection. This is bad news, because it turns out boys are less resilient to adverse childhood events than girls are.

As the boys enter elementary school, they start out just a bit behind their female peers in relational and emotional intelligence, but that gap widens alarmingly as they grow. What that leads to are boys who crave connection and intimacy but don’t know how to get it. Their friendships are more “shallow” than girls’ friendships, often leading teen boys and men to put all their emotional eggs in the romantic relationship basket. And teens and men who don’t have a romantic relationship pretty much have nowhere to go to get their emotional needs met.

This is because from childhood on, girls are bombarded with stories and cultural assumptions that reinforce the idea that relationships are important. Boys, on the other hand, are fed a series of adversarial stories that require some sort of “victory” of the hero and rarely address relationships at all. Boys are ill-equipped to attain what countless researchers have found to be the most defining feature of a happy life — strong connection with others.

As I read, I thought about how my aversion to violence had kept stereotypical “boy” media to a minimum in our household. I thought about how frequently I had held a tantrumming child on my lap and named his emotions for him: “You’re so disappointed that you lost your toy,” or “You’re frustrated because the paper keeps ripping.” I thought about how many times I had asked, when correcting a thoughtless behavior, “How would you feel if someone did that to you?”

In addition to being a feminist, I’m also a highly sensitive person. Having two boys in the house, especially during the long winter months, can be frequently overstimulating. Although my sons are fairly cautious, the highly physical ways they prefer to play often have me tensing up with fear of broken bones or concussions. Jumping off the stairs, headstands, constant wrestling. Before reading this book, the story I often told was that I had given birth to boys to force me to confront (and maybe someday overcome?) my own defects. My anxiety around chaos. My need to have everything planned. My tendency to hold on too tight to the people I love. Raising boys would put me face to face with my shortcomings again, and again, and again.

But reading BoyMom has given me a different perspective. My feminist rejection of both toxic masculinity and gender essentialism gives my sons more room to develop as whole human beings. My total cluelessness about boys allowed me to see them as people, first and foremost, with the needs for love and connection and safety that all people have. I made it a priority to communicate love, to hold them accountable for misbehavior, to listen patiently in their most vulnerable moments. I am not a perfect mom by any means. My high sensitivity makes me prone to snap at them when things get too chaotic, and taming my temper is a constant battle. But the things that I AM good at — the long, honest conversations, the silent holding of my sons against me while their bodies relax before bedtime, the curation of diverse and relevant reading material — may be just the things boys need most.

Thanks to Ruth Whippman, I have a different story about myself as the mother of boys. And it goes like this:

Maybe I am the right person for this job after all.